Exploring the Volcanic National Parks (by Mike Baker)

August marks the 102nd anniversary of three of our “hottest” parks: Haleakala National Park, Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, and Lassen Volcanic National Park.

Though both Haleakala and Hawai’i Volcanoes were established as their own separate parks in 1960 and 1961, their geologic magnificence led Congress (with the influence of Congressmen and their wives having dinner cooked over steam vents years before) to create Hawaii National Park in 1916, which included both volcanoes.

Maui’s Haleakala is a dormant volcano that last erupted in 1790. Northern California’s Lassen Peak is an active volcano that most famously erupted in 1915. Hawaii’s (or The Big Island’s, whichever you prefer) Kilauea has been erupting since 1983 and most recently and dramatically starting three months ago in May 2018.

Haleakala

Most experience Haleakala National Park for the first time in the pre-dawn darkness after a 37-mile drive up the twisting Haleakala Highway. Unless you’re already starting from upcountry, the drive from sea level to the Haleakala Visitor Center covers 9,740’ of elevation – loosen those water bottle caps and open the valves on those Camelbaks!

The summit area’s weather is definitely unpredictable. Even if it looks clear down below, by the time you arrive, you might be greeted by wind-driven rain and those who’ve covered themselves in their hotel’s extra bedding. Yet the faint red glow to the east gives you a sense that something amazing is about to happen.

On a clear morning, sitting quietly atop Pa Ka’oao – the small hill just above the visitor center – soon reveals why Haleakala is known as The House of the Sun.

According to legend, the demigod Maui’s grandmother assisted him in capturing the sun and slowing its travel across the sky, lengthening the day. The cloud formations that can obscure the crater appear to serve as both stage and actors, retelling the story as the drama unfolds. Once the sun peeks over the clouds, you can spot both Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the Big Island 90 miles away to the southeast.

Sometimes local tour guides can be heard chanting soft prayers of respect for Haleakala’s ancient grandeur as the sun rises and begins to shed light into the vast crater that slowly comes to life in vivid color.

Most take in the spectacle of the crater and then depart, but poles, boots, sunscreen, and plenty of water let you escape the crater crowd as you descend on the Sliding Sands trail.

Soon enough, Maui’s endemic Silversword begins to dot the trailside and you feel like you’re in a foreign world, part black wasteland of Mordor and part red and rust Martian landscape.

For most morning hikers, a journey down into the crater means a trip to see Kalu’Uoka’O’O cinder cone intimately. From the observation platform at sunrise, the cinder cones appear to trail off into the distance and it’s hard to gain perspective until one is standing near them. Although the cinder cone only has a 30’ prominence, it sits the highest at 8,350’.

More adventurous hikers can apply for one of two backcountry cabins on a first-come, first-served basis, which enables primitive camping farther within the crater, and which also makes hiking down the eastern slope of the volcano through Kaupo Gap achievable. Good logistics planning back near sea level – a waiting vehicle – means you can visit the Kipahulu Visitor Center and walk to the seven Pools of Ohe’o. Famous for locals jumping into the pools from the surrounding rocks, the pools themselves have been closed since January 2017 due to the danger of rockslides after historic rainfalls. The area can also be accessed via the famous Road to Hana which winds all the way around the northeastern side of the island.

But at 8,350’ at the cinder cone, there’s 1,550’ of elevation that must be gained to return to where you started, so, unless you’re super-fit, it’s best to start back up the Sliding Sands trail again. It will take twice as long going back up as it did coming down due to altitude, which should factor into your travel plans.

When departing, it’s also a good idea to take in the views at the Kalahaku and Leleiwi Overlooks. By that time, most of the tourist buses have already left, so the overlooks aren’t usually crowded.

A fitting end for the morning is to stop at Kula Lodge halfway down the mountain to stop for breakfast, where one can commune with the Nene – the Hawaiian goose.

Kilauea

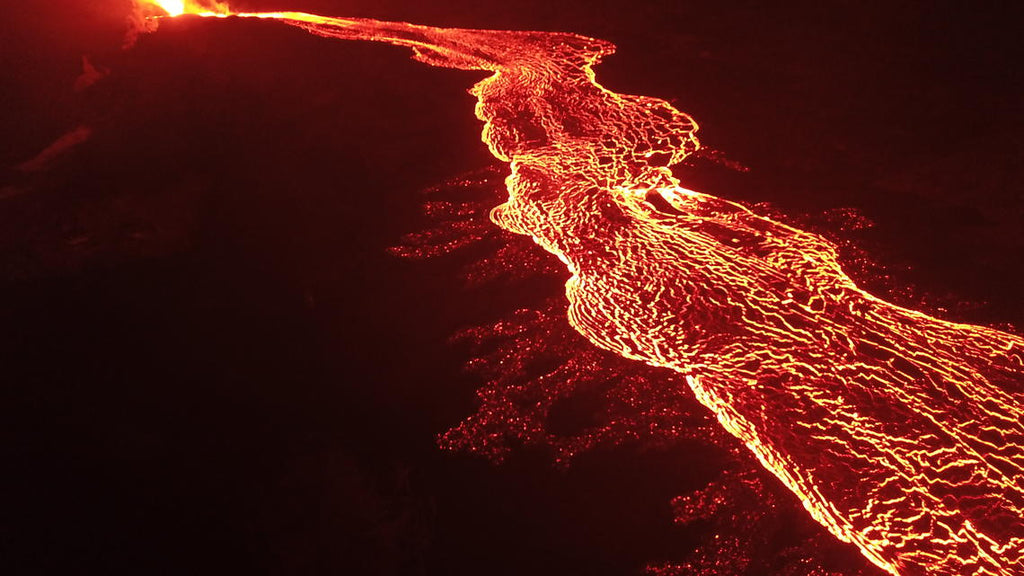

Just three months ago, the lava level in Halemaumau crater in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park fell dramatically, followed by explosions, earthquakes, clouds of ash and gas.

The National Park Service closed the park on May 11, 2018 due to safety concerns. The lava level of nearby Puʻu ʻŌʻō crater also emptied, and the ensuing 20+ fissures that opened and oozed lava for the last three months have changed eastern Hawai’i’s landscape again.

But what can you see if you still want to visit the park?

Officially, the Kauki Unit of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park remains open, which is located an hour south of the Visitor Center on Highway 11. Far from the danger of flying lava bombs, laze, and sulfur dioxide, Kahuku is also a place where the park’s volcanism can be seen. Several miles of hiking trails cover the 1868 lava flow area. There is a two-mile, three-hour guided hike through the area themed around the area’s human history. The grassy rise of Pu’u o Lokuana cinder cone can also be hiked, its summit providing views of the surrounding Ohi’a trees, which are the first to appear after fresh lava flows have cooled. The key to Hawai’i’s watershed, the trees are currently under assault from a fungal disease known as Rapid O’hia Death.

Highway 11, which passes through the park, remains open for through traffic, though there is no recreational stopping allowed on the road shoulder. Driving through this area bears its risks, as there are two buffer zones around the crater: a one-mile zone radius around the crater with risk of large boulder rockfall danger and four-mile radius around the crater – that encompasses portions of Highway 11 leading into and out of the park visitor center – with risk of marble-to-pea-sized rockfall danger.

UPDATE: The NPS has announced they plan to reopen parts of the park on September 22nd, 2018.

Lassen Volcanic

One of two volcanoes to erupt in the continental United States during the 20th century (Mount St. Helens being the second), Northern California’s Lassen Peak is one of the largest plug dome volcanoes in the world. Though the volcano’s position marks the southern terminus of the Cascade Mountain range, there’s been no end to Lassen Volcanic National Park’s geologic activity. The size of its geothermal area is second only to Yellowstone.

You know you’re getting close to the park from the east (Red Bluff or Redding) when you start to see fields full of lava boulders. Even without the benefit of having been to the park before, it’s easy to infer: “something big happened here!”

Typically, one enters the park from the south, arriving at the Kohm Yah Mah-Nee Visitor Center, which has an interpretive path behind the building that affords a view of the remnants of Brokeoff Mountain: Pilot Pinnacle, Mount Diller, and Diamond Peak. This is when you realize that Lassen isn’t just one volcano: the entire area is full of volcanoes! All four types are present: shield (Mount Harkness), composite (Brokeoff Mountain), cinder cone (Cinder Cone), and plug dome (Lassen Peak).

But volcanoes aren’t the only active reminders of the park’s past. The Lassen Volcanic National Park Highway winds its way through some of the most memorable features, offering more than just a visual sensation. The eyes aren’t the only ones to “take it in” — the nose is going to smell it and the ears are going to hear it soon!

Just up the road from the visitor center is Sulphur Works, one of the park’s many hydrothermal areas. Steaming fumaroles, boiling mud pots, and sulfurous gas provides a multi-sensory experience of Earth’s power to destroy and create. But be careful, getting wet on this ride is one thing and getting burned is another! There are numerous warnings to stay on established trails and boardwalks.

The most well-known hydrothermal area in the park is clearly Bumpass Hell, named after Kendall Vanhook Bumpass, who broke through the thin ground hiding a boiling pot of mud below, scalding him badly. So don’t be a Bumpass: stay on the trails! Unfortunately, Bumpass Hell is undergoing a major boardwalk renovation, so the area is currently closed.

Farther up the highway provides an excellent view of the southern face of Lassen Peak from the shore of Lake Helen. The key feature of Lassen Peak’s southern face is Vulcan’s Eye, a dacite lava formation with a circular feature that suggests the eye of the Roman god of fire gazing upon his handiwork.

Ahead to the north around the eastern side of the volcano reveals Lassen Peak’s Devastated Area. It was here in 1915 that a blast of steam shattered the volcano’s plug, resulting in a massive explosion of super-heated water, volcanic gas, and rock that devastated its northeastern slope, famously captured by photographer B.F. Loomis.

Once you pass the site of the park’s “youngest” geologic feature, Chaos Crags, and enjoy views of its six lava domes, a nice, practical reminder of the Earth’s geologic transformation can be found at the Manzanita Lake Campground once you are ready to depart — a gas station!

← Older Post Newer Post →